CA

ON

럭키 여행사

전화: 416-938-8323

4699 keele st.suite 218 toronto Ontario M3J 2N8 toronto, ON

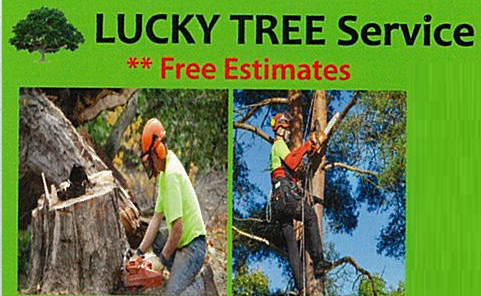

럭키조경 & 나무자르기

전화: 647-564-8383

4699 Keele St. Unit 218 Toronto, ON

호남향우회 (토론토)

전화: 647-981-0404

7 Bishop Ave. #2411 Toronto, ON

한인 시니어 탁구협회

전화: 647-209-8933

1100 Petrolia Rd Toronto, ON

4.jpg)

골프 싱글로 가는길

전화: 647-291-2020

115 York Blvd Richmond Hill Toronto, ON

최고의 POS시스템 - 스마트 디지탈 POS

전화: 416-909-7070

4065 CHESSWOOD DR. NORTH YORK Toronto, ON

0.jfif)

싸인건설

전화: 416-909-7070

4065 Chesswood Dr. North York, ON

0.jfif)

토론토 기쁨이 충만한 교회

전화: 416-663-9191

1100 Petrolia Rd Toronto, ON

K-포차 ...미시사가(만두향프라자)

전화: 905-824-2141

169 DUNDAS ST. E. #7 Mississauga, ON

조준상 (로열르페이지 한인부동산 대표)

전화: 416-449-7600

1993 Leslie St. Toronto, ON

부동산캐나다 (Korean Real Estate Post)

전화: 416-449-5552

1995 Leslie Street Toronto, ON

.jfif)

대형스크린,LED싸인 & 간판 - 대신전광판

전화: 416-909-7070

4065 Chesswood Drive Toronto, ON

It would be a place where all the visitors including me share the life stories and experiences through their activities,especially on life as a immigrant.

Why don't you visit my personal blog:

www.lifemeansgo.blogspot.com

Many thanks.

블로그 ( 오늘 방문자 수: 165 전체: 267,728 )

두뇌기능향상용 알약을 사용해야 할까?말까?-윤리적문제

lakepurity

2008-12-14

과학자들이 오랜 연구끝에 만들어질 단계에 있는 뇌기능향상용 복용약을 생산해야 좋은가?

아니면 그른가?를 놓고 의견이 분분한것같다.

노인들의 뇌기능 상실을 막고, 긍극적으로는 치매현상도 줄일수 있는, 뇌의 활동을 향상

시키기위한 두뇌약이 건강한 노인들을 상대로 시험단계에 있다고 한다. 이러한 시험적인 도전에

윤리적인면에서 상당한 의견들이 조심스럽게 학자들간에 제시되고 있다한다.

그러나 이기사를 읽은 네티즌들의 의견은 거의가 다, 특히나 사회적 활동이 왕성한,74세된

노인은 '내가 그 시약에 첫번째 경험자가 되고 싶다'고 강한의욕을 나타내는등, 도덕적인

면에서도 긍극적으로 나타나고 있다.

조심스럽게 반대의견을 내는 학자들은 '남용'을 우려하고 있는것 같다. 예를 들면,

잠을 못자는 환자용 복용약이 label을 떼어내고, 팔리면서 남용되고 있고, 또 반대로

'Modafinil'을 복용하면 90시간 이상을 뜬눈으로 지낼수 있다고하는데, 이런점들을 악용하면서

다른데에 건강을 해칠수 있다는 추측이다.

학자들은 지난 20년 넘게 뇌기능이 포함된 신경에 관한 깊은 연구를 해 왔다고 한다.

아래 기사를 읽으면 자세한 내용을 이해할수 있을것으로 보인다.

The dilemma of pills that boost brain power

Brain drugs to alleviate the forgetfulness of old age will be the first of their kind targeted to healthy people. An exploration of the ethics of the new neurological frontier

December 14, 2008

Momoko Price

TORONTO STAR

"We have brains that are about as large as they can be, in evolutionary terms.

However we do have the prospect, with pharmacological interventions - of altering that state.

Now, will that be good for people?"

Julian Savulescu, Director of the Oxford Centre for Neuroethics

Over the past 20 years, scientists have made great progress diagnosing and treating the brain. In another decade one of its most persistent and irritating problems - the forgetfulness that comes with age - may soon be fixed with little more than a daily pill.

But beyond alleviating absent-mindedness, drugs for "age-associated memory impairment," or AAMI, seem poised to alter our standards for cognitive well-being. Because drug treatment won't just be about disorders - it could be about making healthy people better than well.

DECADES AGO, Dr. Thomas H. Crook began investigating the condition now known as AAMI, with the hope of helping the aged. In 1985 he invented it, in a sense, while working at the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health "invent" is an odd way to put it, but prior to 1985 age-associated memory impairment simply did not exist as a medical condition.

In a way, Crook - founder of clinical research companies such as Psychologix, Inc. and Cognitive Research Corporation - simply defined a syndrome we know all too well: the phenomenon of getting dumber as we get older.

Crook had taken notice in the 1970s while studying Alzheimer's disease. "I started to think, This is odd isn't it, when we treat cancer, heart disease or anything else, we treat as early as possible," he recalls. "Where here, we don't really call something a disease and initiate treatment until the patient is really quite profoundly demented. They don't know where they are, what season it is, who's the president of the country. I mean, does that really make sense? Isn't that akin to treating cancer on the deathbed?"

So Crook looked at memory loss across the age span. The results were striking. Our ability to remember names, for example, declines 60 per cent between the ages of 25 and 75. That's a lot of embarrassing party situations.

By 1985, Crook and his colleagues had characterized AAMI as significantly poor memory performance in healthy people at or above the age of 50, compared to young adults. By 1994 it was included in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) as "age-related cognitive decline."

What's unusual about AAMI is that, despite its inclusion in the DSM, it's not an illness. But that's no reason not to treat it, says Crook.

"This is a condition that is encoded in such a way that it is not a psychiatric disorder," he says. "But it is a developmental condition that merits attention and treatment.

"I've debated these issues many, many times over the years, and it's become an easier argument than it used to be. People, typically neurologists, used to say, `But it's normal! But it's normal!' Well, yeah, so is the body ravaging bones for calcium in post-menopausal women! It's a normal thing, but we don't just sit there and let it happen."

DR. PETER REINER, professor at the National Core for Neuroethics at the University of British Columbia, believes the very fact that AAMI is so widespread is what makes drugs to treat it controversial.

"If it's a serious disease that you are developing a drug against, society does and should tolerate some degree of side effects for that treatment," he explains. "On the other hand, this is not a serious disease, this is not even by definition a disease; it is a change in cognitive status that occurs with aging.

"Because these drugs are very likely going to be pursued widely by the public, they really need to be safer than most drugs usually are when they get approved."

Having watched dozens of prospective AAMI drugs fail clinical trials, Crook believes American approval standards are rigorous enough to account for this. Reiner, a Canadian, isn't so sure. "The regulatory authorities have so much to do already that they really don't have resources to go and think about this in advance.

"That's the mandate of people in the field of neuroethics. That's the way it works until we get to the point when drugs actually are being put in front of the regulatory authorities."

HUNDREDS OF ACADEMICS recently flocked to the headquarters of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C., to discuss the ethics of changing our brains. At last month's inaugural meeting of the Neuroethics Society, Julian Savulescu, director of the Oxford Centre for Neuroethics, defended cognitive enhancement in a debate with bioethicist Carter Snead, who works as an expert consultant to The President's Council on Bioethics.

"My position is that cognitive enhancement offers the prospect of a number of potential benefits," Savulescu says, recalling the debate. "What we currently have at the moment is a situation where our cognitive capacities are essentially limited by our evolutionary history. ... Basically, we couldn't have evolved much larger brains and greater cognitive capacities than we have now.

Now, with "pharmacological interventions and ultimately with genetic and other more fundamental biological interventions," he says, "we will be able to surpass what nature has given us."

Citing not only drugs for AAMI but also the wildly popular Modafinil, a sleep-disorder drug whose off-label use has skyrocketed in recent years, and notoriously abused drugs such as Ritalin and Adderall, Savulescu argues that we're already at a point where we can enhance our cognitive abilities.

"Now, will that be good for people?" he asks. And in his view, "there's good evidence to think that it will be."

Savulescu describes a future in which people could pursue better jobs and be less accident-prone. A world of greater economic productivity (studies have shown, he says, that a three-point jump in IQ across the population would result in a 1.5 per cent increase in GDP); a world in which the need for welfare could drop off significantly.

Moreover, Savulescu thinks people will pursue these drugs regardless. And if we don't start addressing the high demand that's already in the black market, a veritable health crisis could erupt.

To Savulescu, the problem isn't the drugs, it's the lack of drug research on healthy people who want them. "We need to start taking this seriously and saying, 'What are the benefits and risks of these sorts of things in normal people?' " he says. "Otherwise people just can't make informed decisions as individuals whether to take them or not. And we can't make social decisions about whether they're good for society or not."

CARTER SNEAD, who argued the opposing view, had a tough go at the debate. "`As I understand it,'" he recalls saying, "my charge is to argue in favour of intellectual mediocrity, drowsiness, depression and grief!' That's not a winning hand!" he laughs.

Still, Snead can't help but be concerned with society's tendency to dismiss means and ends when tempting new technologies arise. In other words, we don't discuss what we're trying to achieve and how we plan to get there.

Take Modafinil, whose black-market use among academics was documented in a survey by Nature this year. "Modafinil supposedly can keep you up for like 90 hours," Snead says, alluding to an experience one of his students had with the drug.

"I think there are social consequences of a society where people are expected to stay up for 90 hours at a time. You could argue, well, they'll be more efficient and they'll have more time for their families, but it might have a really distorting effect," he says. "People work too much ... they don't spend enough time attending to their own personal needs, and you would worry that something like this would aggravate that.

"What does a society look like where people stay up for 90 hours straight and then sleep for eight hours and then do it again? That worries me a little bit."

But the heart of the problem, and what Snead and Savulescu argued for the better part of the debate, is a fundamental lack of coherence between what biomedical treatments are now able to offer and what we need.

In a society where the medical profession is more acceptant of patient autonomy than ever before and profit-driven pharmaceutical companies can sway consumers with ads, Snead worries about the consequences of punting something as tantalizing as "a better brain" to the free market. Because, really, what is "better"? A competitive edge at work? A more manageable disposition? If we move beyond the conventional rule of "If it ain't broke, don't fix it," whose rules should we follow?

"The problem is nobody agrees on what health means," Snead says. "Nobody agrees on who's permitted to decide or define what health means, and as a result we have what I think is a crisis in the profession of medicine, where the profession has become untethered from its animating purpose, because nobody agrees on what that purpose is."

After debating for hours, Savulescu and Snead came to the humble realization that the real debate of what defines human well-being has barely begun. But if we don't start talking about it, it'll be hard to put the biomedical toothpaste back in the tube.

BECAUSE IN A WAY, cognitive enhancement is not as new as one might think.

Reiner reminds us that whether it's been through education, the printing press or computers, "a major part of what we have done over the last 10,000 years, as we have been emerging from an uncivilized state into a civilized state, has been on the backs of enhancing our cognition.

"You could say that cognitive enhancement is the ultimate in human aspiration in many ways."

Taking our brains into our own hands, whether it's with memory drugs or Modafinil, might be seen as the next step. Whether we do it responsibly, on the other hand, is not nearly as assured.

Toronto Star