CA

ON

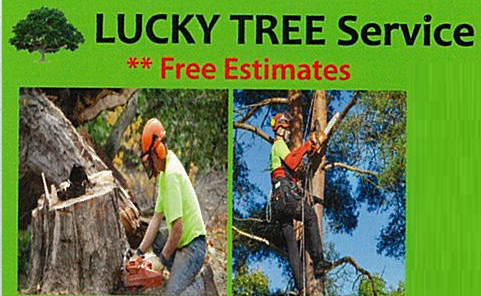

럭키조경 & 나무자르기

전화: 647-564-8383

4699 Keele St. Unit 218 Toronto, ON

부동산캐나다 (Korean Real Estate Post)

전화: 416-449-5552

1995 Leslie Street Toronto, ON

.jfif)

한인 시니어 탁구협회

전화: 647-209-8933

1100 Petrolia Rd Toronto, ON

4.jpg)

싸인건설

전화: 416-909-7070

4065 Chesswood Dr. North York, ON

0.jfif)

대형스크린,LED싸인 & 간판 - 대신전광판

전화: 416-909-7070

4065 Chesswood Drive Toronto, ON

한인을 위한 KOREAN JOB BANK

전화: 6476245886

4065 Chesswood Drive Toronto, ON

.jpg)

K-포차 ...미시사가(만두향프라자)

전화: 905-824-2141

169 DUNDAS ST. E. #7 Mississauga, ON

고려 오창우 한의원

전화: 416-226-2624

77 Finch Ave W #302, North York Toronto, ON

골프 싱글로 가는길

전화: 647-291-2020

115 York Blvd Richmond Hill Toronto, ON

럭키 여행사

전화: 416-938-8323

4699 keele st.suite 218 toronto Ontario M3J 2N8 toronto, ON

호남향우회 (토론토)

전화: 647-981-0404

7 Bishop Ave. #2411 Toronto, ON

토론토 민박 전문집

전화: 416-802-5560

Steeles & Bathurst ( Yonge) Toronto, ON

It would be a place where all the visitors including me share the life stories and experiences through their activities,especially on life as a immigrant.

Why don't you visit my personal blog:

www.lifemeansgo.blogspot.com

Many thanks.

블로그 ( 오늘 방문자 수: 44 전체: 267,607 )

알맹이 빠져 버린 대통령 선거-NY times 전제.

lakepurity

2007-12-18

Election in South Korea Is Missing Its Suspense

Seokyong Lee for The New York Times

Article Tools Sponsored By

By NORIMITSU ONISHI

Published: December 17, 2007

SEOUL, South Korea - South Korea’s presidential elections have tended to be bruising, down-to-the-wire contests that exposed voters’ ideological schisms and raw emotions over the country’s tortured relations with North Korea and the United States.

But this time, in a campaign that has otherwise failed to grab the electorate’s attention, there has really been only one issue: the economy. And the only suspense had been whether the clear front-runner’s campaign would be derailed by charges of stock manipulation.

As candidates crisscrossed the country in the final days before the vote on Wednesday, it seemed almost certain that Lee Myung-bak, a former mayor of Seoul and a construction industry executive nicknamed the “Bulldozer” for his take-charge style, would be elected.

With Mr. Lee holding a nearly 30-percentage point lead in opinion polls by three major news organizations last week, his aides were talking confidently of capturing more than 50 percent of the popular vote. In South Korea, the candidate with the most votes wins, but no one has been able to garner more than 50 percent since South Korea’s democratization in the late 1980s.

“We are predicting between 50 percent and 55 percent,” Chung Doo-un, a top aide to Mr. Lee and a National Assembly member, said Sunday. “I think this will be unprecedented in the history of South Korea.”

Late Sunday, though, Mr. Lee’s seemingly assured victory was challenged by President Roh Moo-hyun, who instructed the justice ministry to reopen an investigation into accusations that Mr. Lee had been involved in manipulating the stock of an investment company, BBK. On Sunday morning, a video clip had surfaced in which Mr. Lee, who has denied any involvement with the company, appears to be claiming to have founded it in 2000.

On Monday morning, the justice ministry, which had cleared Mr. Lee of the charges this month, said it stood by its earlier judgment.

Mr. Lee’s spokesman, Kim Heon-jin, said Monday that Mr. Roh’s move had been politically motivated and that “possible editing” had been done to the video.

It was not clear how the president’s reopening of the investigation would affect Mr. Lee, whose approval ratings had suffered only slightly in the weeks before he was cleared by prosecutors. Barring a last-minute reversal, Mr. Lee, 65, is likely to be elected to succeed Mr. Roh, who is limited by the Constitution to a single five-year term.

Five years ago, Mr. Roh, a human rights lawyer and a former lawmaker, won with a message of asserting independence from the United States, reconciling with North Korea and emphasizing social equality, but his ratings have fallen because of popular discontent over his economic policies.

In his campaign appearances, Mr. Lee, the candidate for the conservative Grand National Party, capitalized on that anger, as he attacked the Roh administration and presented himself as the candidate best qualified to handle the economy.

“I will create a world where young people can choose good jobs,” Mr. Lee said to a raucous crowd at a market in the southeastern city of Taegu last week. “To people selling things, those running small- and medium-size companies, I will create a world that works. I will unfailingly revive the economy.”

Mr. Lee’s agenda for accomplishing that mission ranges from the orthodox, like lowering corporate taxes, to the grandiose, like building a huge canal to connect two rivers and form a unified shipping route from the southwest to the northeast. He has also pledged to realize what he calls his “Korea 747 Vision” — increasing economic growth to 7 percent a year, doubling per capita income, to $40,000, within a decade and moving the country’s economy, now the world’s 13th biggest, to the seventh largest.

The message has resonated in a country increasingly squeezed between high-tech Japan and low-cost China. While multinationals like Samsung are doing well, small- and medium-size businesses find it increasingly difficult to compete against counterparts outside the country because of rising labor costs. While the stock market is booming, economic growth has slowed. Soaring real estate prices have made housing unaffordable for average Koreans, and youth unemployment remains high.

Although many of the economic difficulties lie beyond the control of any president, voters blame Mr. Roh for the malaise.

Mr. Roh ended up losing even his most ardent supporters — young voters who, in 2002, were attracted to his image as a reformer and rallied for him on the Internet and on the streets.

“I was very excited in 2002 but feel that he didn’t accomplish much in the economy,” said Lee Jong-youl, 32, an office worker browsing in a bookstore in downtown Seoul on Wednesday. “For someone in the middle class or lower, like me, I feel that income gaps have widened.”

Mr. Lee said he had barely followed this election and was undecided about whom to support, but he added that the front-runner was “not bad.”

Yoon Yae-young, 31, a graduate student, was not supporting Mr. Lee but explained why others were. “The young believe that he’ll revive the economy and create jobs,” Mr. Yoon said. “They blame Roh Moo-hyun for everything. There’s a joke that even when something bad happened in your personal life, you blamed Roh Moo-hyun.”

Mr. Roh was so unpopular that members of his Uri Party created a new party, the United New Democratic Party, in an effort to disassociate themselves from him. Still, the new party’s candidate, Chung Dong-young, 54, ranks a distant second in polls.

Mr. Lee’s focus on bread-and-butter issues stands in sharp contrast to that of Mr. Roh and his predecessor, Kim Dae-jung, both of whom had the clear objectives of democratizing South Korean society and reconciling with North Korea.

Mr. Lee supports engaging North Korea and promises substantial economic assistance if it abandons its nuclear arms program. But he does not make emotional appeals to Korean unity, as Mr. Roh did, and takes a harder rhetorical line by insisting that he will not shy away from taking tough measures against North Korea.

“Lee Myung-bak is perceived as being much more of a pragmatist than an ideologue,” said Lee Nae-young, a political scientist at Korea University who has been conducting opinion polls on the election. “He appeals to the general public because his views are perceived as being closest to the general public’s views.”

Since the last presidential election, he said, Korean public opinion had shifted to the center while the left and right has shrunk. Seoul’s policy toward North Korea has not come to the fore as an issue in this election because differences between conservatives and liberals have narrowed considerably since 2002, he added, and a general consensus over the engagement policy has emerged.

Indeed, Mr. Lee’s Grand National Party itself has moved toward the center. In the 2002 and 1997 elections, it selected as its standard-bearer Lee Hoi-chang, a right-wing politician with a hard-line stance against North Korea.

Last month, Lee Hoi-chang, 72, unexpectedly declared his candidacy, this time as an independent, saying he was displeased with the front-runner’s policy toward North Korea.

“Lee Myung-bak’s policy toward North Korea is a copycat of the sunshine policy,” Lee Hae-yon, a spokeswoman for Lee Hoi-chang, said of the engagement policy toward the North. “Our candidate believes that the main goals should be to denuclearize North Korea and for its regime to change.”

Lee Hoi-chang trails, in third place. But analysts say he could eke out a few points on Wednesday and rob the front-runner of his goal of winning more than 50 percent of the popular vote.